History

Back to NewsroomPrivate Albert George Pegram and the Battle of Polygon Wood

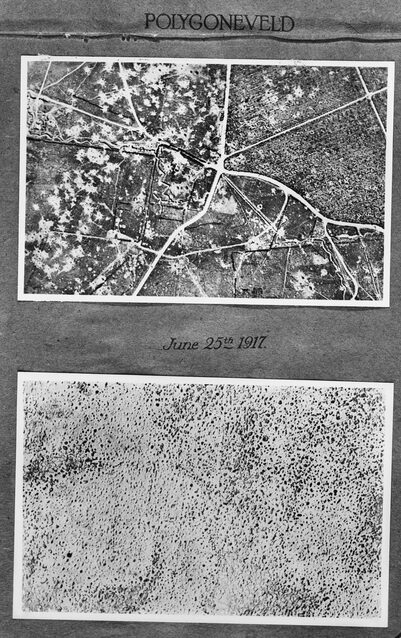

In 1917, in the midst of the Third Battle of Ypres, troops of the Australian Imperial Force were engaged a few dozen kilometres east of the town, near the town of Zonnebeke, in Polygon Wood. They found themselves fighting in an almost lunar landscape, an expanse of craters dotted with tree stumps as far as the eye could see.

The Battle of Polygon Wood is remembered as a military success, but it came at a high cost, with almost 4,000 casualties in the 5th Australian Division alone. The battle was the second of three major attacks planned by British General Viscount Herbert Plumer, along with the Battle of the Menin Road and the Battle of Broodseinde.

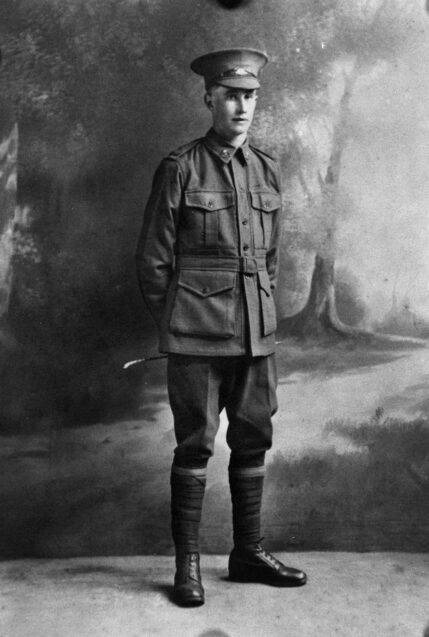

Among the soldiers of the 5th Division was Private Albert Pegram (service number 3204) who served from the age of 18 with the 55th Battalion. Motivated by the idea of reuniting with friends and cousins already serving in France, he embarked from Sydney on 11 November 1916.

The Third Battle of Ypres was already well under way by the time the 4th and 5th Divisions were ordered to attack Polygon Wood on 26 September 1917. Little did they know that the Battle of Polygon Wood was to become one of the most successful Australian engagements.

Previous attempts to seize sections of the German line had been overambitious resulting in the infantry advancing beyond the range at which their own artillery could protect them from German counterattacks. The result being that ground captured was often lost.

Plumer was an advocate of ‘bite and hold’ tactics. These involved a short advance by the infantry behind a heavy artillery barrage followed by the infantry digging in on the position gained, while a barrage placed in front of them prevented the Germans from counterattacking. There would be a several days’ break to prepare for the next step, crucially allowing artillery to be brough forward, then the process would be repeated.

This battle, in the midst of the 3rd Battle of Ypres, was the 5th Division’s first major engagement since the terrible losses suffered at Fromelles in July 1916.

That day the 5th Division, supported by British troops on its flanks, succeeded in taking German positions throughout the wood, including the Polygon Butte, an artificial mound used by the Belgian Army in the late 19th century for rifle practice.

This high ground occupied an important strategic position for the German Army, offering an extensive and commanding view of the surrounding area and blocking Allied advances towards the Passchendaele ridge.

After taking the wood, the 55th Battalion consolidated its new positions and extended them to prevent a German counter-attack.

Although the successful capture of Polygon Wood and the Butte was a proud moment for the 5th Division, it came at a high price with Imperial forces suffering some 15,000 casualties, more than a third of which were Australian. The 5th Division incurred almost 4,000 casualties and the 4th Division, which attacked alongside the 5th Division, lost around 1,700.

Private Pegram was one of these. Shot in the stomach by a German sniper, Private Pegram was seriously wounded, as he jumped across an exposed trench with his section. One of his cousins who was with him at the time, wrote to his parents to explain the terrible ordeal he had been through. Private Pegram was evacuated to the 17th Casualty Clearing Station near Popperinge, where he died of his wounds two days later.

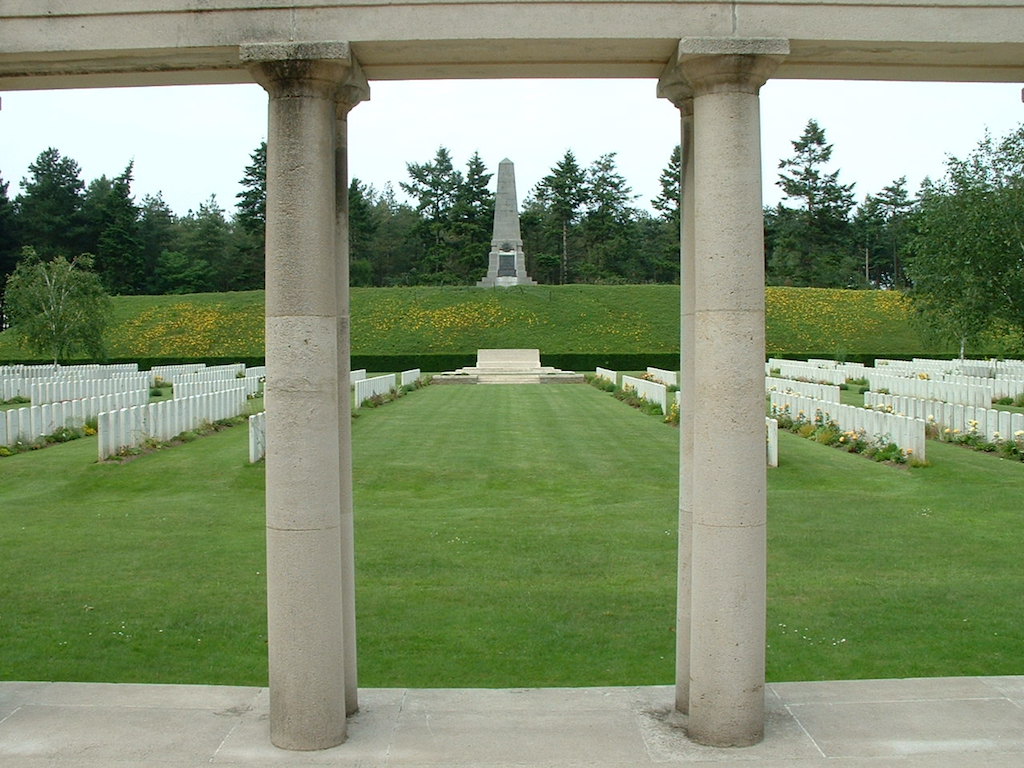

Private Pegram is buried in Lijssenthoeck Military Cemetery, west of Ypres. Private Pegram’s loss was devastating for his family, who were never able to visit his resting place. His nephew was born on the day of his death and bears his name. Private Pegram’s father never forgave himself for signing his son’s enlistment papers and his mother was buried with his war medals and commemorative plaque.

Since 1919, the 5th Australian Division Memorial has stood on the Butte, overlooking the Buttes New British Cemetery, nestled in Polygon Wood. The remains of 2,000 soldiers were interned here after the war, and almost 1,700 have never been identified.

‘‘In his lonely grave he lyes far from all he loved so dear.’’